In March, New Zealand became the first country to legally recognise a river as a living being. Te Awa Tupua is now acknowledged as a legal person and ancestor of the Whanganui tribe. Identifying a waterway as a single, though complex, entity challenges the colonial concept of a river as a natural resource to be exploited. What if the Murray-Darling River was a person? How differently would we relate to Australia’s largest river system?

‘Troubled Waters’ completes a triptych of exhibitions at the Samstag Museum of Art exploring humanity’s relationship with rivers and oceans. ‘The Ocean After Nature’ and ‘Countercurrents’ were exhibited earlier this year for the Adelaide Festival. ‘Troubled Waters’ is an interdisciplinary project curated by Dr Felicity Fenner, director of UNSW Galleries, in collaboration with Professor Richard Kingsford from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Centre for Ecosystem Science. It seems fitting the exhibition travelled from New South Wales to South Australia, given its commissioned works also follow the Murray-Darling River from source to sea.

Janet Laurence, River Journey, 2016, multimedia installation based on audio and visual research archive of Professor Richard Kingsford. Installation view at UNSW Galleries. Courtesy of silversalt

‘River Journey’ forms one of three parts to the exhibition. Multimedia works by five contemporary artists respond to UNSW’s research into human impact on water environments. Andrew Belletty’s installation appeals to all the senses. A flyover along the river is enriched by an immersive soundtrack. Tactile elements invite curious fingers to interact with the sweat of the river.

In contrast, Janet Laurence’s glass vessels emphasise the unnatural nature of purified water. Flowing water is replaced by manufactured white cloth. Translucent organisms shadow-play across the surface. This is the cleansed, filtered, artificial relationship we have with our water. This is a river with amnesia; water that’s forgotten who it was.

Photographs from Tamara Dean, Nici Cumpston and Bonity Ely complete ‘River Journey’. Dean’s rosy portraits of researchers in the field bestow their occupation with divine properties. In one of her images three disembodied heads bob on ruffled waves, a new breed of scientific sirens at the Coastal and Regional Oceanography Lab.

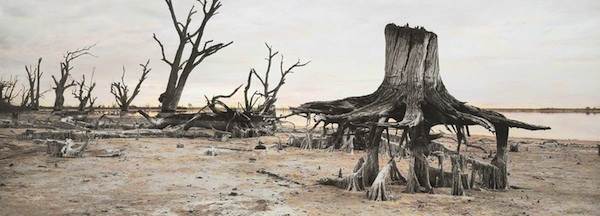

Nici Cumpston, Ringbarked II, Nookamka Lake, 2009/2016, crayon on pigment inkjet print on Hahnemuhle paper. Courtesy the artist and Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, South Australia

Ely and Cumpston are interested in the loss of habitat along the river itself. Ely documents rough mangrove roots eaten alive by acidic waters. Cumptson concentrates on the Murray River’s iconic eucalypts. These gumtrees were the proverbial canary in a coal mine, among the first species impacted when poor resource management reduced the river to a drizzle. If the Murray-Darling was a person, Cumpton’s photographs are the post-mortem portraits of an ecosystem that died of thirst.

Bonita Ely, Bottle Bend Grid, 2008, inkjet print on photo rag, 80 x 122.5cm. Courtesy the artist Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, South Australia

The final two sections of the exhibition are cinematic works from Australian filmmaker Georgia Wallace-Crabbe and British filmmaker John Akomfrah. Wallace-Crabbe’s The Earth and the Elements (2015) occupies five screens representing the elements of wood, fire, earth, metal and water. It is the culmination of her PhD about Australia’s mining boom, following the trade of natural resources to fuel urban development in China. The panoramic display makes for a confluence and conflict of images that convey the industrial momentum of the enterprise. Repeated viewing is rewarded with new revelations each time.

Georgia Wallace-Crabbe, still from ‘The Earth and the Elements’, 2015, 5-channel video. Courtesy the artist

John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea: Oblique Tales on the Aquatic Sublime (2015) is an international drawcard following its success at the 2015 Venice Biennale. Three cinema-sized screens bring suitable grandeur to mass migration and thundering seas. The ocean’s abundance is juxtaposed with commercial exploitation of its resources by man, in keeping with the exhibition’s environmental message. Recreations of coastal landscapes from British paintings reference Romantic notions of the sublime, subverted by Akomfrah’s criticism of colonial ambition to conquer and control nature.

The two standalone cinema works are impressive for the scale of their production as well as their presentation. Sea-faring continues to influence Australia’s identity as an island nation, from international trade to immigration policy. But ‘River Journey’ has local significance in South Australia, the first state to witness human impact on the Murray-Darling River. Belletty’s perpetual, twisting river may lack the drama of Akomfrah’s towering waves and cracking ice, but is just as sublime.

Liv Spiers is a writer based in Adelaide.

Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art

Until 9 June, 2017

South Australia